Polling

Explain the methods

In our audience research, we consistently hear that people want more information about the methods that are used to design and distribute polls, and about the ways polling data gets analyzed. Doing this helps audiences think critically about polls, and makes media organizations more credible in the eyes of the public.

Here are some things you can do to explain methods:

1) Tell audiences whenever quantitative data comes from a survey. Don’t just focus on the results. In headlines, that means using the word “survey” or “poll.”

DO THIS

"26% of job switchers regret joining the Great Resignation, survey finds: ‘They’ve sobered up’"

DON'T DO THIS

“Millions of Americans Regret the Great Resignation”

DISCUSSION

Headlines that relay findings from surveys or polls should always inform audiences of this fact. In failing to do so, the "don't do this" example encourages passive acceptance of the claim made in the headline. It may also suggest that the journalist reporting on the survey is in agreement with the finding, and that this finding is above scrutiny. To combat the assumption that polls are objective and authoritative, include words like “survey finds” or “survey indicates” in your headlines. Doing this will promote critical thinking about polls, and contribute to the broader goal of increasing adults’ statistical literacy.

2) Be specific about the exact questions in the poll, and the options respondents could choose. Don’t assume your audiences will know these things.

DO THIS

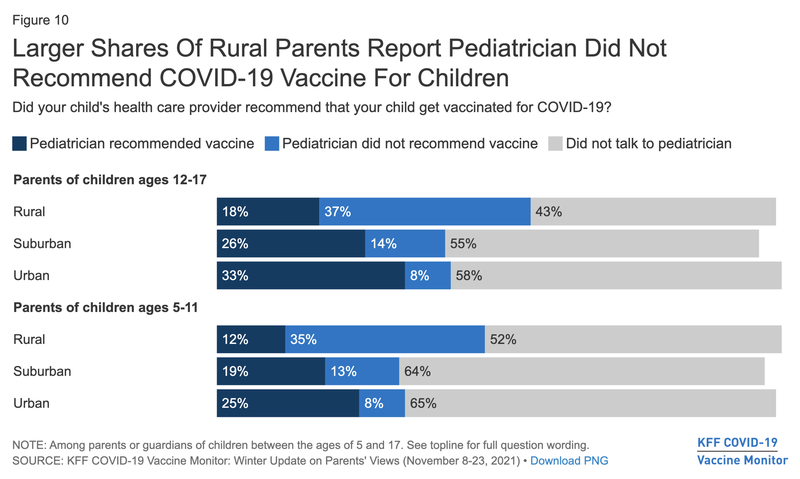

This figure makes it clear that only about half of parents consulted their pediatrician about vaccinating children against COVID-19.

DON'T DO THIS

Meanwhile, another sentence on the same data: "[N]early 40% of rural parents reported that their child’s pediatrician did not recommend a COVID-19 vaccine, compared with only 8% of parents in urban communities."

DISCUSSION

Our research consistently shows that audiences will infer that the only possible answers to a yes-no question were “yes” and “no” unless you tell them otherwise. As such, when seeing the "don't" text above (for example), they would assume that about 60% of rural parents (and about 90% of urban parents) reported that their pediatrician did recommend a COVID-19 vaccine. To avoid this kind of mistaken inference, inform readers about the percentages of respondents who chose “don’t know” or “not applicable”—especially when these answers comprise a significant number of total responses. If a large number of people said they were unsure or the question was not applicable, that matters for interpretations.

3) Tell audiences who conducted the poll and who paid for it. Don’t assume your audiences will know if a pollster has competing interests. If there is a good reason to trust or mistrust that pollster, spell it out.

DO THIS

A report includes the headline "Republican-funded poll finds one of the closest battlegrounds in the country favors GOP Rep. Young Kim by 16 percent."

DON'T DO THIS

A headline about a survey conducted by a major hotel chain reads, "Americans Admit They Need a Break From Family After Less Than Four Hours This Holiday Season"

DISCUSSION

There are many different ways of constructing polls, and sometimes, the people funding these have a vested interest in seeing a particular result. Of course, this is not always the case. However, to encourage a healthy amount of skepticism toward polls in general, and to support audiences’ critical scrutiny of them, it is important to let people know the individual or organization behind a particular poll. The "don't do this" example fails to do this, and in so doing, may gloss over the fact that hotel chains have a vested interest in research showing that people need vacations and getaways. Firms sometimes write deliberately misleading questions with the goal of eliciting particular results. Marketing and political polling firms, in particular, have a vested interest in presenting their work as rigorous research—but it often isn’t. To help readers decide for themselves how valid a given poll’s results are, always share information about who backed and designed it.

- Previous

- Introduction

- Next

- Explain uncertainty